Recently I made a presentation at IDCI about the basic differences between simulations and games, meant predominantly for beginner learning designers. At the end of the presentation I spoke about five ways to bring more gaminess into the learning interactions being designed by the IDs. One point I made was about the use of ‘narrative’ or ‘stories’. (I use them interchangeably, as they mean pretty much the same to me, perhaps wrongly.) While I ran out of time there, a nice discussion with great points about stories and storytelling being made. I wanted to quickly recap some important concepts I uncovered during my research about the use of narratives in learning.

Storytelling has been a pedagogical instrument since time immemorial; recently, we are also seeing stories and the use of narrative increasing in elearning. As more digital technology becomes mainstay in our lives, our ability to tell stories digitally has surpassed what could have been imagined just a generation ago. Think about the phones, the cameras, and the multi-functional computers we carry around. Each is a tool that can be leveraged for creating or telling stories.

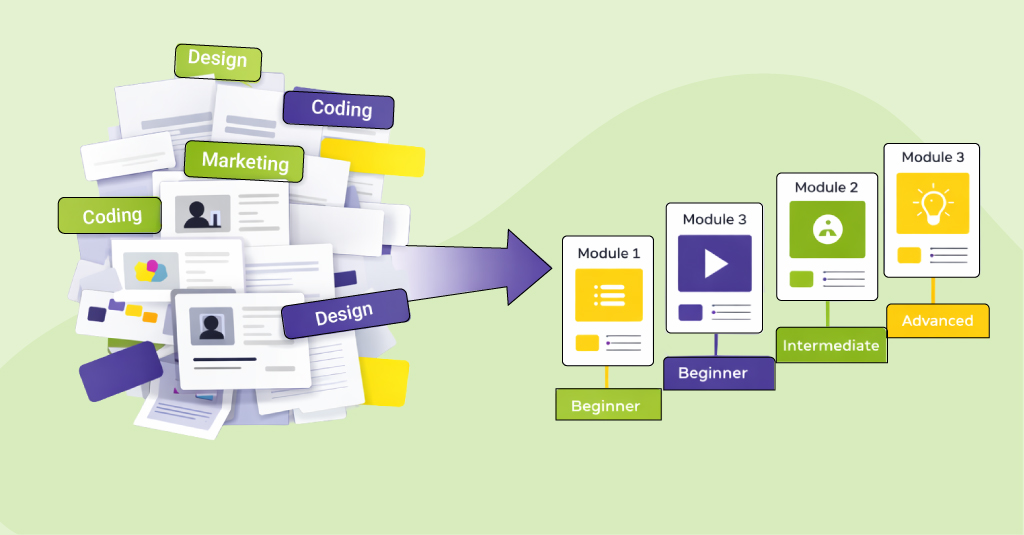

One of the new pedagogical models based on story-telling is Story-centered curriculum, proposed by Roger Schank in 2007. Another is scenario-based curriculum development, suggested by Ray Bareiss Sukhjit Singh (2007). Learning through stories is the main thought in either model. Stories have been used as instructional methods because they co-opt crucial aspects of human communication: information, knowledge, context, and emotions. In most opinions, designers agree that storytelling or narrative in some form or the other is necessary to produce engaging elearning. Typical elearning content that just transforms existing media into digital form obviously don’t work to tell digital stories. Such a conversion based approach lacks the element of flow, has little true engagement and will bore learners.

Storytelling principles have been in existence and articulated since Aristotle. To hold and maintain the learner’s attention, the narrative must connect with the learner’s emotions and create emotional movement. Any learning that associated with stories, particularly those that provide emotional experiences, is persistent – this makes for better recall.

Robert McKee’s expounded principles for writing effective stories. Instructional designers would do well to keep these in mind when writing stories. To begin, McKee defines emotional charge as the level of built up emotion. He also states that for a story to be engaging, the emotional charge must constantly change. In effect, to create an engaging story it must flux between positive and negative emotional charges. Positive charge can be associated with being happy; negative emotions in real life lead to being unhappy.

To achieve emotional movement, McKee proposes five stages for designing the “spine” of a story:

1. Inciting incident

2. Progressive complications

3. Crisis

4. Climax

5. Resolution.

The inciting incident gets the story moving. In a problem-centric view, this is the basic problem that the protagonist is attempting to solve. In a story designed for learning, unlike the usual presentation of facts and concepts, the solution to the problem is what contains the instructional content and learning. Progressive complications and conflict make the story emotionally charged and is key to maintain interest. The implication that every problem that the protagonist solves raises a new problem; McKee calls it the “Law of Conflict.” McKee makes an interesting point that storytelling is a “temporal art” like music; and, conflict is very important for good stories. (Conflict is a very important element of games too). Crisis is that stage of the story where the protagonist seems to be surrounded by insurmountable problems. Climax is the stage where emotions reach their peak. Resolution is where all story problems are resolved.

A story designed and told for learning must include comprehensive and explicit resolution, answering every problem raised in the narrative structure. Extending (or rather subtending) what McKee states – the narrative for a story designed for learning must include a minimum three stages: inciting incident, progressive complications, and resolution. For eLearning content to be effective some narrative structure is essential, rather than just a drab presentation of facts and concepts.