When was the last time you were so involved in what you were doing that you forgot yourself? You lost track of time? You were ‘in the zone’?

All of us can recall such moments – while reading a book, listening to music, playing a sport, in an online computer game. But I wonder how many of us have felt this during an online course, or inside a classroom when being taught?

As learning designers and developers, we’d want to create gripping experiences that draw in learners and keep them up till two in the morning (like video games do to so many). Such a state of sustained attention and engagement is called “flow”, a term coined by positive psychology researcher Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his work “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience“.

Being in flow, according to Csikszentmihalyi, is the optimal learning experience. He describes flow as a mental state where an individual is so completely caught up in an activity that they lose track of time. All their attention is focused on the activity; there’s no attention left or available for anything else. The activity itself is intrinsically motivating. It is challenging, yet not out of reach; it has a clear goal, and is carried out as per a set of rules, with continual feedback.

Can we design learning experiences that nudge learners into a state of flow?

In one of our recent weekly sessions, we discussed the application of some of the key factors associated with flow that might apply to eLearning. With so many more of our team members playing digital games nowadays, we think we know why we get so caught up in them.

1. Having a clear goal in sight

It’s important for learners to know where they are headed, and why. Tell them the overall goal and purpose, and how they can go about achieving it. Explain how the program is structured. Clarify what they can expect and what is expected of them.

In a game, a user is generally presented with a mission or challenge. This mission often contains or represents the win state, and maybe an associated reward which also acts as a motivator. The mission is generally broken into smaller sub-missions, and rules, patterns, and functions are discovered by the learner as they explore and play.

2. Knowing where you stand at all times

Learners should know how they’re faring, how far they’ve come, how much distance remains to be covered – all on a continual basis. After any action, they should also know immediately how well they did on that action.

Games generally provide two types of feedback: continuous and discrete or specific feedback based on individual successful or failed actions. Users can readjust or correct as required in the subsequent action or where possible, reattempt or redo the action.

3. Achieving a balance between ability and challenge

Know your learners. A program shouldn’t be too easy, or learners will get bored. Nor should it be so difficult that learners get discouraged. Pre-tests can help identify areas of focus for individual learners, and learning paths and content should be sequenced accordingly. Content should be properly scaffolded and structured such that those with more experience can skip the basics.

Games present a challenge while building user confidence; the challenge is achievable, but not comfortably so, and increases with each level. Since skills grow with practice, increasing levels of challenge that unlock progressively make perfect sense.

The time allocated to clear a level is also a factor that can build confidence and help build skills, as is the amount of help provided. An unskilled user may have more time to master a level, initially, and be given more hints; as they move to a higher level, they are given less time and less assistance to clear preceding lower levels.

4. Having a sense of control

Learners like to make choices, decide what to see and when to see it, explore, and discover. Usability plays a part here too – the GUI and interactive elements should be intuitive in design, clear, and unambiguous – in other words, a button should look clickable and its function should be clear. There shouldn’t be any doubt about it.

Games offer users a high degree of control. Users choose where to go, what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and must deal with the consequences of their choices. Objects behave as per their function, for example, clicking on a door opens it – unless it is locked! There is also consistency of behavior – once you figure out how an object or type of object behaves, you can expect it to continue to behave in a similar manner in all its instances.

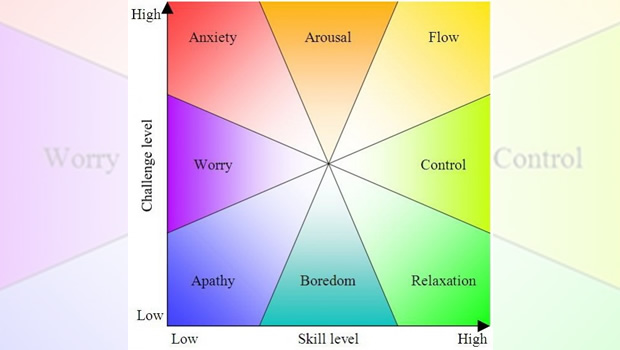

In a TED talk, Csikszentmihalyi mentions two complementary areas from which it is easy to get into a state of flow.

The first is arousal, which is where the challenge is slightly higher than the current skill level. You can move into flow by increasing your skill a bit, but for now, you’re just beyond your comfort zone. Most people, according to Csikszentmihalyi, learn when in a state of arousal.

On the other side is control, where the challenge isn’t quite so compelling since skills are now up to the mark. Moving back into flow simply requires challenge to be increased a bit.

Should we be aiming to put learners into a state of arousal when it comes to acquiring a brand new skill, and a state of flow when it comes to consolidating a recently gained skill?