If you’re on Twitter and have missed Spymaster – where in the world have you been? All the rage last week, you’ve probably seen the many #spymaster tweets from tweeps in your network. You’re into it, or just plain confused about what the objective of the game is; either way, there’s no way you can ignore it’s huge presence on Twitter.

So what’s Spymaster about – quite simply its leveraging Twitter’s people network, using Twitter APIs to provide a Mob Wars style game experience. By using OAuth , the game is directly linked to your Twitter account; you’ll use the same profile as on Twitter, no need to create an account unlike other web-games. You’ve probably been invited, click through an invite and you’re in Spymaster-land.

Choose your agency, from amongst the British M16, the American CIA and the Russian FSB. Like most strategy games, you have to do some tasks like collecting dead drops or assassinating individuals, you get experience points and money–in the currency of the agency you represent. With this money you can buy weapons and other goodies on the black market to increase your attack and defense points. The key – this is a social game, your attack and defense points are implicitly related to how many people are following you on Twitter and how many of those you manage to convince to join the game. I sent out several dozen invites, got less than half to join.

It’s interesting to examine the immense popularity of this game; in conversation with AV Flox on her blog, Darshana Jayemanne of the University of Melbourne, makes an interesting comment about that:

“The game is similar to some other stuff that’s going around on other sites, and there’s a lot that could be said in general about why these games work. In particular though, I think the sync between the espionage theme and Twitter in particular works very well–Twitter itself feels kind of clandestine, like you’re immersed in these minutiae of other people’s lives as well as sharing select bits of information yourself.

The Twitterverse exists parallel to the mundane world, a bit like Mail Art or the Trystero in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. The stress of just how much to share is central to the spy thriller genre in which various bait-and-switches, mirroring and foreshadowing techniques are similar to the feeling you get piecing together some-one’s life from a stream of terse messages.

An unexamined life is not worth spying on.

The other thing is that we all tend to carry around more devices than any ’60s supervillain anyway. And we love to use them for fun as well as business, to use our devices in support of our vices. It’s a quasi-fetishistic activity, in fact, what Walter Benjamin would have called “the sex appeal of the inorganic.””

That’s a fascinating comment, about the nature of Twitter – clandestine yet immersed in minutiae of people’s lives. That’s one thing that makes Twitter so powerful, it appeals to our nature of wanting to know and share, especially about others. In response to a question about what ‘drives’ a game like Spymaster satisfies:

“It’s all in the design. Games are set up to organize desires around reward structures. So the design sets up the drive. Once you’re hooked to the reward structures, and can compare your success or failure to others (through points or money or what have you), it’s a self-sustaining process. Or so the designers hope. The “become a vampire/werewolf/zombie/banker/whatever” game apps on Facebook got old quickly–their scope was too limited.”

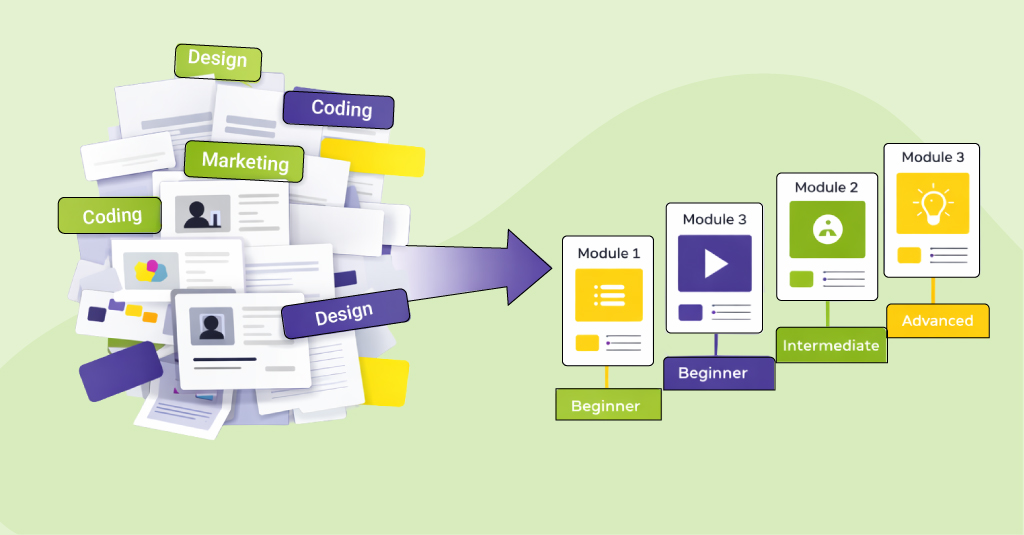

I’m trying to draw parallels in the design of instructional games. How are ‘learning games’ set up to organize desires through rewards? Do we do enough to design reward structures that engage the learner? One aspect that occurs to me immediately is the need to include features like leader boards in learning games where players can compare and contrast their performance. Another is that there has to be a feature that lets players actually observe others performance in the game environment. Such observation helps learning, and let’s players analyze success strategies; understand some implicit game environment rules, and master advanced mechanics in the game.

As I keep mentioning in reference learning game design, keeping a game SIMPLE is never easy. Spymaster did well to keep everything in balance and engaged to the extent that the game is addictive. Try Spymaster, we’ll be seeing more and more of these asynchronous network based games. It’s only a matter of time before their mechanics and architecture seep into learning games.