Once digital systems are running, day-to-day work on the shop floor involves fewer visible interruptions. Variance narrows, alerts fire on time, and exceptions appear contained when viewed through operational metrics.

When learning data is reviewed alongside those same systems, however, it often reflects an older operating model, one where completion rates remain flat, and certification records show currency without signaling deeper capability movement. Learning systems, in many cases, continue to track attendance and validation rather than how judgment is developed under digitally mediated work.

The disconnect usually becomes visible later, during handoffs, overrides, or audit reviews, when teams rely on judgment that was never formally developed inside the digital environment. At that point, the limitation is no longer the technology itself, but the learning infrastructure meant to prepare people to work within it.

This blog looks at why digital learning transformation stalls in smart factory settings like these, and how early learning partner decisions shape enterprise digital learning outcomes long before results are formally measured.

How Smart Factory Technologies Are Reshaping Shop Floor Decision-Making

During early production reviews after new systems go live, fewer issues tend to be raised in routine shift discussions. Downtime is lower; alarms are more controlled, and many adjustments that once required intervention are now handled upstream by the system. What changes instead is where attention goes. Operators spend more time deciding whether a signal matters. Supervisors spend more time deciding whether to trust what the system is recommending.

In facilities running MES alongside connected equipment and planning tools, the nature of judgment shifts. Instead of deciding what to do next, teams increasingly decide whether to intervene at all. A scheduling recommendation may be technically sound but locally impractical. A quality alert may be statistically significant but operationally tolerable. These calls sit in a gray space that systems surface but cannot resolve. Standard eLearning, still structured around task execution and recall, rarely prepares people for this kind of judgment-heavy work.

Several changes tend to follow as this becomes routine:

- Decisions that were once embedded in tasks now sit between roles.

- Accountability becomes harder to trace as systems pre-filter choices.

- Experience shows up less as speed and more as discernment.

Over time, this alters how competence is recognized on the floor. Performance depends less on executing known steps and more on understanding how interconnected systems behave under variation. That expectation is rarely explicit, yet it becomes central to daily operations. Learning systems that remain role-based and static struggle to reflect this shift, even when production systems evolve quickly.

As this gap between system-driven work and human readiness widens, questions about skills surface indirect ways. Not as training requests, but as friction in roles that no longer map cleanly to how work actually happens. At that point, eLearning is no longer a support function in the background, but a visible constraint on how effectively digital operations scale.

Why Role-Based Skill Models Break Down in Industry 4.0 Operations

The first signs rarely show up as formal training gaps. They tend to surface when responsibility is discussed after something goes wrong. The system has already intervened in some way, which makes it harder to say who was expected to step in and when. At that stage, eLearning is already part of the problem, because most learning systems still assume stable roles and predictable decision paths.

Roles still exist on paper, but accountability is no longer obvious in practice. Learning frameworks that assume stable role boundaries struggle to keep pace with this shift.

At this point, the issue is not only role clarity, but whether learning systems are designed to develop judgment across boundaries that no longer stay fixed.

In digitally mediated manufacturing environments, skills do not sit cleanly inside job titles. Operators are expected to decide whether system behavior is acceptable, even when no explicit limit has been crossed.

Supervisors spend more time interpreting signals coming from planning, quality, and maintenance systems that do not always align. These expectations emerge faster than most eLearning models designed to adapt.

Most of these expectations are never written down. Teams learn them by working with the systems over time. Certain alerts are treated as noise. Others are known to require attention, even if the system does not escalate them clearly.

That knowledge circulates informally and unevenly. When digital learning systems rely primarily on predefined content and static pathways, this kind of situational knowledge remains invisible.

While production systems continue to adjust in small increments, learning content typically remains unchanged until gaps surface through incidents, audits, or reviews.

Manufacturing upskilling efforts often stay focused on equipment operation and procedural compliance. On the floor, however, work depends more on how people read situations across systems, something that is rarely trained formally or reflected in records.

This is where gaps appear between what eLearning certifies and what operational readiness actually looks like.

As dependence on this informal experience grows, the impact extends beyond productivity. It begins to surface in safety, quality, and compliance discussions, where judgment gaps are harder to work around and less easily absorbed.

At that point, learning decisions start to affect operations directly, even if they are still handled as a separate function inside the organization.

How Safety and Compliance Exposure Changes in Digitally Mediated Factories

Safety and compliance issues in smart factories rarely surface as sudden failures. They tend to appear as small inconsistencies that are easy to dismiss at first, especially when systems appear to be in control. An alert is acknowledged late because the system has already corrected the condition. A deviation is logged but not reviewed because output stayed within limits. Individually, these moments seem contained. Over time, they accumulate.

During this period, system behavior may shift repeatedly while learning guidance stays static, increasing reliance on individual judgment rather than shared practice. When learning systems focus on validation rather than interpretation, they do little to shape how these decisions are handled before they show up in reviews.

Once production decisions are filtered through MES, analytics, and automated controls, responsibility for safe operation becomes distributed.

In these conditions, learning systems influence how consistently judgment is applied, not by enforcing rules, but by shaping how people interpret signals under system control.

- Systems flag conditions, but people still decide how seriously to treat them.

- Alerts increase in volume, but escalation paths often remain informal.

- Response patterns begin to vary by shift, team, or supervisor rather than by policy.

- Similar signals are handled differently depending on who is present.

Compliance reviews are usually where this drift becomes visible.

- Audit trails show that required steps were followed.

- The reasoning behind certain actions is difficult to reconstruct.

- Decisions were made, but the logic stayed with the individual.

- Learning records capture completion, not interpretation.

In some plants, incident investigations trace back to moments where no rule was violated, yet judgment filled gaps left by incomplete guidance. The system behaved as designed. The human response was not consistently shaped.

This is where digital manufacturing learning becomes tied directly to risk management.

- Safety depends less on knowing procedures.

- More on recognizing when system behavior signals something unusual.

- Even when thresholds are not crossed.

As factories rely more on judgment exercised under system guidance, the limits of one-time certification become clearer.

- Credentials confirm baseline knowledge.

- They say little about response consistency.

- Or how people act when conditions fall outside expected ranges.

Why One-Time Certification Stops Working Once Systems Start Changing Faster

Certification still plays a role in manufacturing environments, but its limits become more visible once production systems stop holding still. The issue is not that certification is incorrect. It is that certification assumes a fixed reference point, while digitally mediated operations continue to evolve in small but frequent ways.

Most digital learning systems that support certification are built around the same assumption of stability.

In plants where MES logic, alert thresholds, and planning rules are adjusted incrementally, certified knowledge ages unevenly. Some parts remain valid for long periods. Others lose relevance quietly, without any clear signal that retraining is needed.

Credentials confirm that someone was ready at a point in time, even as daily decisions begin to rely on newer system behavior.

Learning platforms rarely surface this drift, because they track completion rather than context.

This creates a predictable pattern that shows up across plants. Capability decays not because people forget, but because the environment changes around them. Certification verifies exposure, while performance depends on repeated judgment under current conditions.

When learning systems do not adapt at the same pace as production systems, this gap widens without being explicitly managed.

In manufacturing environments like this, digital learning transformation is less about changing platforms and more about keeping learning aligned with live system behavior.

Over time, certification becomes easier to satisfy than to trust. It meets audit requirements, but it offers limited insight into how consistently people respond when systems interact in unexpected ways or when conditions fall outside documented scenarios.

From a learning perspective, this limits visibility into actual readiness.

As digital manufacturing environments continue to shift, this gap becomes harder to overlook. Learning discussions begin moving away from periodic validation and approaches that allow skills to be exercised, observed, and adjusted alongside system changes.

This is where simulation and scenario-based learning move from being supplemental eLearning formats to core mechanisms for keeping capability aligned with live operations.

Simulation and Scenario-Based Learning as an Operational Requirement

In digitally mediated factories, learning gaps rarely appear as missing knowledge. They tend to surface when teams encounter situations that systems expose, but routine work does not prepare them for. These moments are infrequent, conditional, and difficult to recreate safely in live production.

Simulation and scenario-based learning address this gap by changing how skills are built. Instead of relying on exposure through real incidents or exceptions, learning environments are used to rehearse decisions before those conditions arise. The emphasis shifts away from repeating procedures and toward practicing judgment under system-driven constraints.

This is where eLearning stops functioning primarily as content delivery and begins functioning as an extension of operations. Scenarios are structured around how IoT signals, MES logic, and planning rules interact, rather than around static task flows.

Learners are placed in situations where signals of conflict, data is incomplete, or escalation paths are ambiguous. These are not edge cases. They reflect how work now unfolds on the shop floor.

For this approach to hold at scale, learning systems have to adapt in step with production systems. As thresholds change, rules are updated, or workflows are reconfigured; learning content must change as well.

This shifts digital learning transformation away from course creation and toward maintaining a learning ecosystem aligned with current operating conditions.

Data plays a quiet but central role in this process. Learning systems begin to track not just completion, but exposure to scenarios, patterns of decision-making, and response consistency over time.

That data informs which scenarios are emphasized, how content is adapted, and where additional practice is required. In this context, simulation and scenario-based learning are not enhancements layered onto existing programs. They become core eLearning methods through which readiness is maintained as systems evolve, rather than validated after the fact.

Continuous Learning as a Production Support System, not a Program

Once simulation and scenario practice are in place, a different question tends to surface around frequency and ownership. In digitally mediated factories, system behavior changes in small increments rather than visible resets. Learning tied to events or certifications struggles to keep pace with that pattern, because it is designed around checkpoints rather than continuous adjustment.

In this context, continuous learning behaves less like an HR program and more like production support. From an eLearning perspective, this marks a shift away from episodic delivery and toward systems that stay active alongside operations.

- MES logic changes introduce small shifts in decision paths.

- Alert thresholds are adjusted without retraining cycles.

- Planning rules evolve while roles remain fixed.

- Teams adapt informally when learning does not move with the system.

When learning systems do not account for these changes, capability development becomes uneven rather than designed.

Knowledge spreads unevenly.

- It follows those who encounter a condition first.

- It depends on who is present during an exception.

- It varies by shift rather than by design.

This is where the limits of static digital training become visible. Without mechanisms to refresh, reinforce, and redistribute learning in response to system changes, readiness becomes dependent on exposure rather than intent.

In plants that treat learning as ongoing support, practice is revisited as systems change. Learning systems are used to adapt content and scenarios in response to updated logic, rules, and workflows.

- Scenarios are updated when logic changes.

- Assumptions are tested again under new conditions.

- Earlier judgments are reexamined rather than archived.

The intent is not constantly retraining, but steady recalibration. Digital learning transformation, in this sense, is about maintaining alignment between evolving systems and human decision-making.

Over time, learning stops signaling completion and starts signaling readiness.

- Readiness to interpret signals.

- Readiness to intervene appropriately.

- Readiness to respond consistently as conditions evolve.

Where Upside Learning Fits in Smart Factory Training and Manufacturing Upskilling

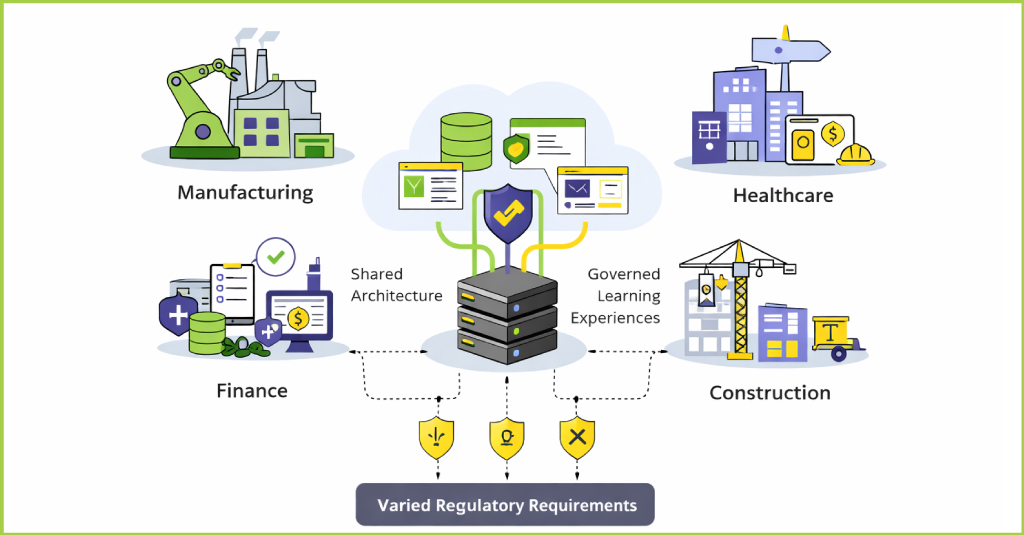

As production systems become more digitally mediated, learning challenges tend to shift from scale to structure. Systems evolve incrementally, while roles remain largely fixed. Learning has to stay close enough to operations to reflect how decisions are actually made, without becoming tied to one-off events or static certification cycles.

Upside Learning operates in this space by designing digital learning environments around production scenarios rather than fixed roles. The work shows how operators and supervisors respond to system signals, handle exceptions, and decide when to intervene as data moves across IoT layers, MES workflows, and planning tools on the floor. Learning is shaped around those moments, not around role definitions that assume stable tasks and predictable flow.

Simulation and scenario-based learning are used to mirror real operating conditions, including variation, incomplete information, and conflicting signals. Learning assets are treated as part of a broader digital learning ecosystem, where content is updated as production logic changes, not after performance issues surface. This allows learning to evolve alongside systems rather than lag behind them.

From an enterprise perspective, this supports digital learning transformation that is practical rather than conceptual. Learning data reflects exposure to scenarios and patterns of decision-making, not just course completion. Capability of visibility improves because learning activity is tied to how people respond under system-driven conditions.

Over time, this approach helps organizations move away from episodic training and toward learning structures that function as ongoing operational support. The result is not faster training delivery, but better alignment between evolving manufacturing systems and workforce readiness.

To discuss learning approaches aligned with smart factory operations, contact Upside Learning.

Frequently asked questions on hyper-personalized skilling

Hyper-personalized skilling is an enterprise learning approach focused on skills, not job titles or course completion. Learning pathways adapt based on what people can actually demonstrate on the job.

Learning personalization organizes content, while hyper-personalized skilling adapts learning based on validated capability and changing role requirements.

Learning personalization fails at scale because static role models, activity-based metrics, and weak governance cannot keep pace with changing work and risk.

Skills mapping defines observable capabilities and enables consistent assessment, governance, and personalization decisions across enterprise roles.

Governance and human validation ensure that skill assessments are trusted, learning decisions are defensible, and personalization scales without fragmentation.

Yes. Hyper-personalized skilling cuts down unnecessary training by recognizing what people already know and focusing only on the gaps that truly matter.

Enterprise buyers should look at how skills are defined and assessed, how decisions are governed, and whether the approach stays consistent across roles, regions, and risk contexts.

Pick Smart, Train Better

Closing Perspective

Hyper-personalized skilling is not about better recommendations. It is about defensible readiness.

Completion can give a false sense of progress. Over time, gaps show up through audits, slower productivity, and repeated escalations to leadership.

Organizations that invest in disciplined skilling design build systems that adapt as the business changes, without losing governance, trust, or control.

At Upside Learning, we specialize in designing enterprise learning systems where hyper-personalized skilling, governance, and measurable readiness work together in regulated, high-complexity environments.

The question is no longer whether learning should be personalized. It is whether personalization is preparing the workforce or simply organizing content more efficiently.

If your organization is reassessing how learning translates into real capability and risk reduction, start a conversation with our learning specialists.