In our previous blog, we discussed how to evaluate the skills of employees against an organization’s needs, commonly known as the skill assessment approach. We focused on self-assessment, observation, and performance-based appraisals to note that a mix-and-match will be needed so that these can together build an all-rounded view of capabilities. Now, it is our turn to build on the other important area, that is, on skill development of the workforce that might be better prepared to confront future demand. What it stresses most, then, is the ways in which skills are best developed, from formal training through constant coaching and follow-up to ensure that employees can learn to use their skills effectively in the real world.

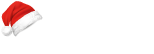

When a need for skills is determined, then there are two options, acquire the skills or develop them. While acquisition of skills is an option, the execution thereof lies with recruitment, which typically is not an area that learning & development (L&D) addresses.

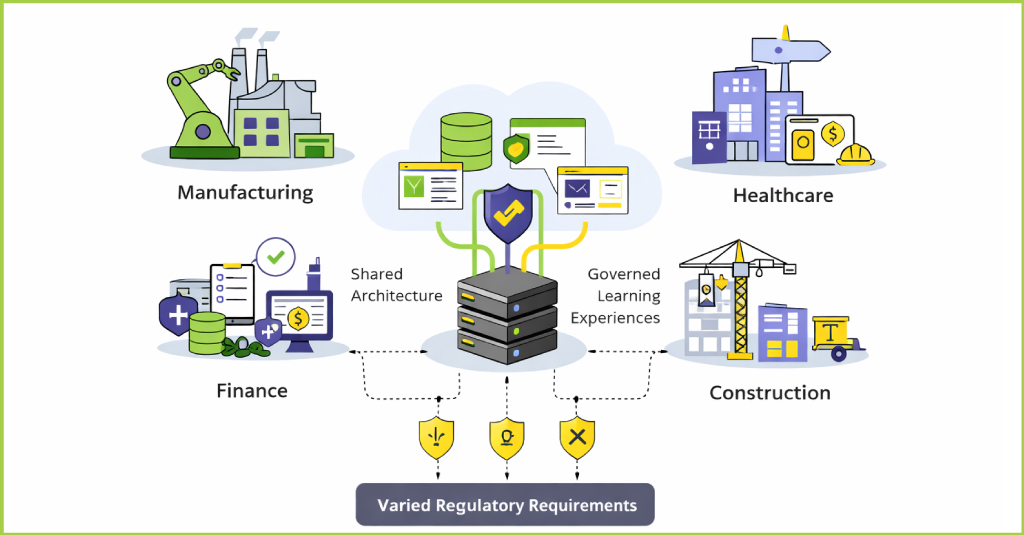

There are strategic reasons to start thinking of skilling as a coherent whole, instead of disparate functions. This would require a reorganization that puts identification, assessment, and recruitment and/or development of skills as a single entity. We’ve identified the tasks required except for recruitment, as that’s an entire suite of its own capabilities.

For the record, in previous discussions on impact and performance, we identified performance support as a viable option. That’s a substitute for skill when skill development is unlikely, costly, or difficult to develop. When information in the world can substitute for skill, it could and generally should. Further, it should be considered as at least part of the solution in any case. For discussion here, however, it will not be mentioned further.

Developing skills is the natural home of L&D. Here, we use our methods of training, coaching and mentoring, and informal learning (including community). Of course, what matters is doing them in ways that reflect what we know from the learning and cognitive sciences to do it right.

Training

There are several ways to deliver training. We typically use an ‘event’ model, whether delivered live face-to-face (F2F) or virtually, or asynchronously. We also should be following up on the learning, through a potential variety of methods.

What should not be done is to consider information presentation as a sufficient mechanism. Perhaps predicated on models of cognition that suggest we’re formal reasoning beings, and therefore with new information we’ll change behavior, such approaches are all too prevalent. However, research tells us that to develop necessary and persistent change, meaningful practice with feedback is required.

There is a benefit from information to support practice, which includes models and examples. There’s also the emotional aspect of awakening learners to the learning, and closing the learning experience. Noting the valuable components and aligning them with learning requires going deeper than considering this all under the rubric of ‘content’. That is, understanding the role each element plays and executing against the nuances is also important.

Overall, training is a powerful tool, but with the caveat: when done properly. There are plenty of resources about how to design training in alignment with the outcomes of research, and these should be consulted and used.

Follow-on

In addition to initial presentation and practice, we also know spacing is required. Reactivation of the necessary components over time is required to take initial learning and turn it into a sustained change. Again, designers must understand the nuances and the roles they play.

Reactivation

As a cognitive underpinning, there are two essential components for learning to occur. Elaboration is how we take an initial idea, and connect it to our pre-existing knowledge. Multiple ways exist to accomplish this. Then, we also need to retrieval practice, asking learners to use the information in context. More valuable here is doing so in ways that are most similar to how information will be applied in practice. It’s not the retrieval alone that matters, but how it is retrieved.

Mechanisms that support elaboration are involved in re-processing the information. Generative approaches, where the learner regenerates the information, include paraphrasing in one’s own words or creating records in other media, typically visual representations such as diagrams ala mind maps, or sketch notes. Another approach is to have the learner use the information to explain things in their past or create ways in which to apply the knowledge going forward.

Retrieval practice benefits from nuances as well. First, just retrieving information just develops the ability to access it, not to use it. Increasingly, the need is to use information is to make better decisions. To develop the ability to apply knowledge to choose courses of action, learners must practice that same. It also turns out that practice applying knowledge also ends up developing knowledge retrieval, so really only the former is needed.

We can also ask questions about how it’s going in the real world. We can ask for plans beforehand, ask if there are barriers as the plans are implemented, and ask about the impact. All of these extend the learning experience. We can do this by connecting with people, or through system-generated prompts. The data from these inquiries is also useful to the organization.

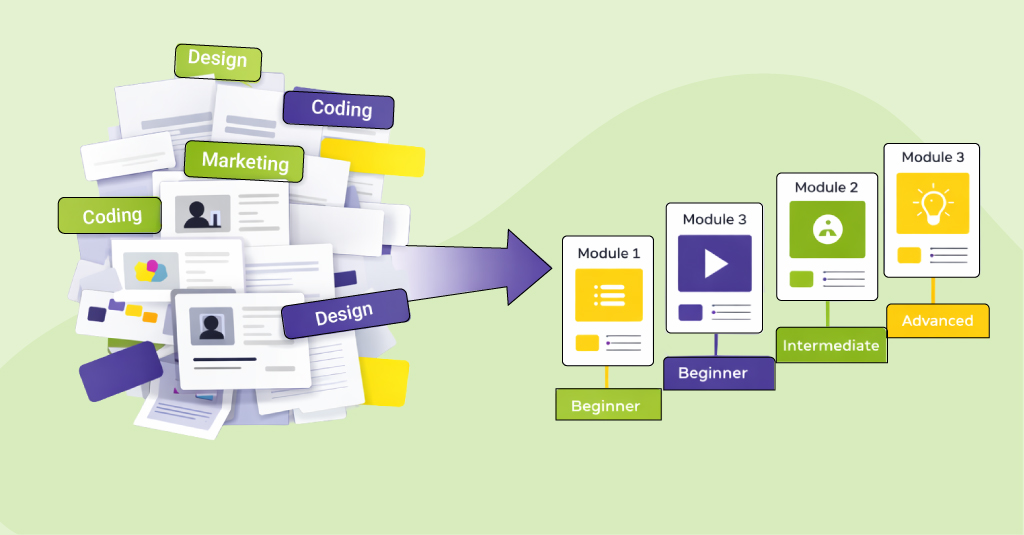

Nuances matter here as well. For one, practice benefits from choosing a suite of contexts that are representative of the situations the learner will likely face. The feedback that explicitly reflects the models about why to do it this way helps, as does facilitating reflection on the models to support decoupling the principle from the immediate circumstance. Another nuance is ensuring that the practice is at an appropriate level of challenge for where the learner is. Practice that is too simple or too complex doesn’t achieve learning outcomes of any noticeable benefit.

Coaching, Mentoring, & Informal Learning

In addition to reactivating knowledge in practice situations, learners are likely to have live opportunities to perform. Feedback from these also accelerates learning. We’ve discussed self-evaluation, but now we’re talking about having others in the loop. Feedback that is domain-specific, and specifically targeted to the domain should precede feedback that asks the learners to self-improve.

Learners, as they progress beyond novices, need different support. Coaching that moves from domain-specific to generic is one approach that has demonstrated value. Another is where learners start learning with and from each other. Having a community where learners can interact, and share their progress and challenges, can be beneficial in the right environment. Similarly, having resources for personalized advancement for learners who’ve developed the necessary foundation can make sense. Here, having resources in any form of media that are curated to be relevant and useful continues the development.

Conscious decisions about how the learner will be supported beyond the event should be part of the learning journey that’s developed. While creating an effective event is a necessary component, it’s not sufficient. For learning goals that are complex, urgent, or infrequent in time, more events may be necessary, so too extended follow-up can be useful and necessary. For instance, in the aviation industry – where emergency procedures are complex in the multiple elements involved, urgent in that people can die if not successfully implemented, and infrequent in that you hope never to see them – ongoing practice is diverse, rich, and continual.

Skills development needs to be done right to be effective. In addition to appropriate learning design and follow-up, it should include any performance support as well. There are processes and practices to assist with and tools to handle some of the details. We know what it takes, so there’s little excuse not to do it right.

Building skills effectively within your workforce goes beyond simple training sessions. It’s about fostering a culture where learning is continuous, aligned with real-world application, and supported by ongoing feedback and coaching. When skill development becomes a strategic focus, it enables teams to perform with greater agility and impact, reinforcing an organization’s core strengths.

To explore more on structuring skilling as a strategic advantage, download our eBook, Skilling for Performance: A Strategic Imperative for Organizations. This resource delves into actionable insights and approaches to help build a workforce that’s not only skilled but prepared for the complexities of tomorrow.