In our last blog, we delved into the intricacies of skill analysis, laying the groundwork for identifying the competencies that matter most within an organization. Now, we turn our focus to the next step: skill assessment. This stage involves evaluating the skills identified during analysis to understand current capabilities and identify gaps. Skill assessment is essential for aligning employee skills with organizational needs, but it presents unique challenges—particularly in a constantly evolving industry landscape where traditional methods may no longer suffice. Let’s explore how to navigate these complexities and build a more accurate picture of workforce skills.

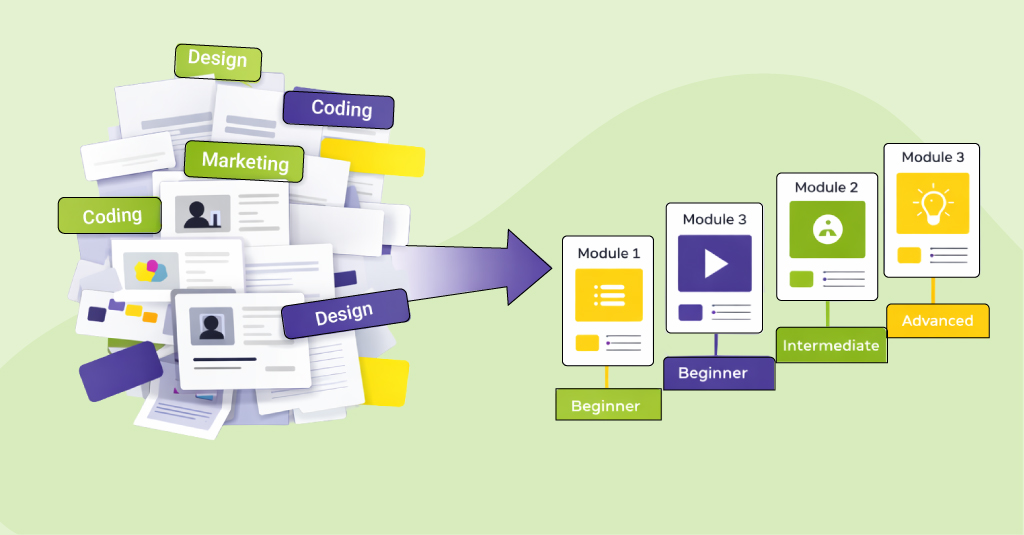

The second step is to assess the skills emerging from the skill analysis. This is a challenge, as there are no specific methods. The information available isn’t typically aligned with this need, or the requirements are considerable. The industry is still in flux here, with a growing recognition of the need for skill alignment, but there’s a legacy of focusing on roles on the organization side and accomplishments on the performer side.

Again, triangulation is a plausible approach in the face of uncertainty. If, as was stipulated earlier, this is the most challenging of the tasks, we will be better served by looking for converging evidence. Thus, triangulation makes sense, and several sources may be needed for different skills.

Types

There are two dimensions that make sense for ascertaining skills. For one, we can determine whether information is objective or subjective. While objective information is a better basis, such measures may not exist. We can have objective data where there are tangible measures, but in lieu of such data, we will have to depend on opinions and do our best to address the potential sources of bias.

A related issue is whether the skill being assessed is for so-called soft skills or hard skills. Hard skills typically can be accurately measured, but skills that are interpersonal in nature may be more influenced by context. Again, we will have to do our best to be as concrete as possible about the skill and the evaluation.

Methods

The methods we have available for assessment are in three sorts. The first two are subjective, self- and other-assessments. Performance assessments are superior but can be costly to develop or acquire and administer.

Self-assess

Self-assessment is the easiest. In short, you survey performers for their evaluation of their own capability, determining their standing on their ability in the skills associated with their demands.

Ideally, you’d provide categorical specifics (“When I work with customers, I a: still struggle to address their emotions, b: have trouble identifying the root cause of the issue, …”), rather than more general categories (“My ability in this is a. Limited, b. Adequate, c. Comprehensive, d. Exemplary”), but the work required is of course more.

There are also sources of bias. Common ones include performers’ own self-awareness, the comfort of admitting to lacks in the cultural context, and more (gender can notoriously affect self-evaluation, for instance).

Such biases are to be expected, and efforts should be made to mitigate the effects. As above, providing clear intent rather than generalities can help, as well as making responding easy as opposed to onerous.

Behavioral interviews can be designed to be more accurate. Here, you are asking the individual to recall situations where they performed and recount the steps and outcomes. These are used in interviewing candidates for positions, and can also be less biased because you’re asking about actual situations. They can be faked, but they’re better than self-assessment.

Observation

A second category is observations. Here the judgement is made by someone other than the performer. This can be superior to self-evaluation, as the individual should be more objective. This doesn’t always hold true, as research suggests some evaluations can say more about the evaluator than the performer!

Options occur here. The evaluator’s relationship with the performer can be one of mentor, supervisor, peer, or customer. The more independent, the better (so independent observers are better than supervisors or customers, for instance; bias is a barrier). Training on the evaluation can also improve the outcomes, but again also requires more development resources.

Also, the data can be in situ, so the observer is in the context, or it can be captured by video or system, such as a log of customer/performer chats. With appropriate evaluation mechanisms, the abstract evaluation of performance can be more objective.

Performance

The ideal assessment is actual performance. This can include evaluating work products, output of systems, and simulated work environments. Here we are either investigating the output of their tasks, or simulated acts.

For one, if performers’ tasks require output, such as documents, these can be evaluated. Ideally, a rubric is created to make it objective. If they’re in any media that establishes an independent representation, these can be evaluated.

If the performers are using a system, their use of the system can also be evaluated. Aggregate data from interactions with systems can be evaluated for efficacy. So, for instance, any application can create its own data, or be instrumented to report usages through systems like the Experience API.

Finally, we can create simulations where learners have to perform tasks that require the application of skills. Creating these simulations can take time, but they may exist from learning development. They may also be purchased.

Other

In addition, people can ascertain skills from credentials as well. Those may use the methods above but frequently have been developed in objective ways. Credentials vary in quality, but the best provide good insight into capabilities.

Together, the evidence captured from these forms of data should give you a picture of where the organization is in its needs for skills both currently required and for future directions.

Navigating the skill assessment landscape indeed is complex, but leveraging a combination of methods can drive the use of a well-rounded understanding of capabilities within your organization. From self-assessments to direct observations and finally, to performance-based evaluations, each method provides unique insights into your team’s current strengths and future potential. By triangulating such insights, you can much better align your workforce’s skills with organizational goals.

For a deeper dive into strategies around skilling, download our eBook, Skilling for Performance: A Strategic Imperative for Organizations to learn how to strategically develop and assess the skills that matter most.