Today, with the increasingly rapid pace of business, mastering the skilling process is important to stay ahead in the race. Organizations must be proactive in identifying, assessing, and developing the skills necessary to address the current demands while developing an eye on future ones. As we wrote about earlier in our blog, The Skilling Process, this entails a strategic approach to skill analysis. In this post, we shall understand how organizations can best perform a skill analysis through multiple sources to gain insight into both current and evolving needs.

As organizations operate and adapt, there are two types of skills they need. First, they need the skills that meet their current needs. While this seems obvious, too frequently organizations are haphazard at best. A second area is that of anticipating future needs. Despite the famous saying “never predict anything, particularly the future”, increasingly we need to be looking forward and anticipating. We also may need a triage mechanism for skills we didn’t anticipate.

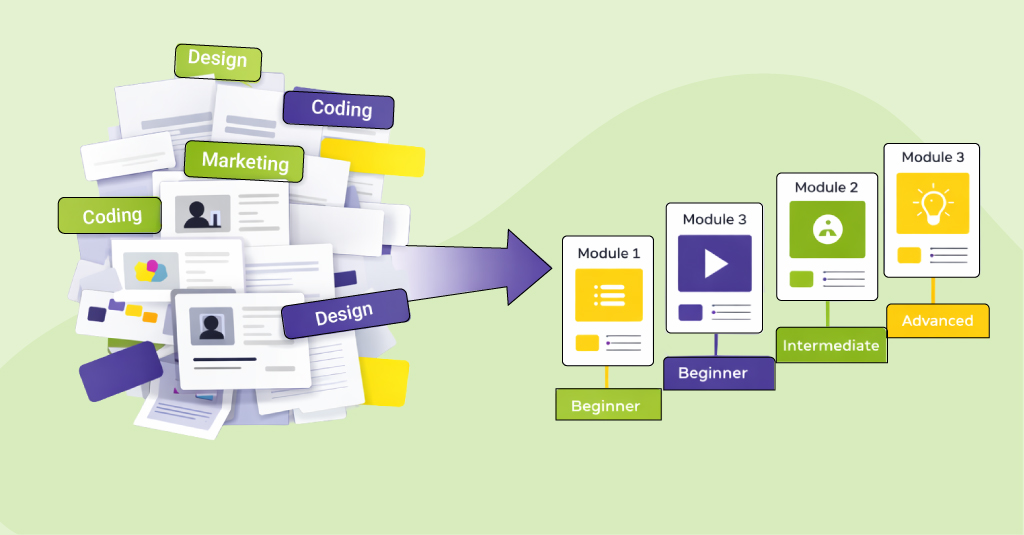

A key element here is triangulation. We should look to multiple sources of information to obtain the richest picture we can. Any single source may be biased by subjectivity or lack of sufficient data. We increase the likelihood of being correct when we compare different sets of information and converge upon a synthesis.

Current Needs

There are potential gaps even in meeting current needs. For instance, our role descriptions may be inaccurate or out of date. Folks may be doing different things than what they were hired, promoted, or reorganized to do.

Still, one source of information is asking folks what skills are needed. Depending on the size of the organization and the need, this can range from focused interviews to a survey. Regardless, we are asking for people’s ideas about what they need. Which isn’t ideal, but is practical, and is one source of insight.

A more direct way of identifying the necessary skills is to look at the flow of work. Here, we’re analyzing the outputs that are developed and the skills that are required to generate them. This is the approach that performance consulting suggests, as suggested in Guy Wallace’s The L&D Pivot Point. The effort required can be substantial, but the insights are highly accurate. This likely makes sense for business-critical operations.

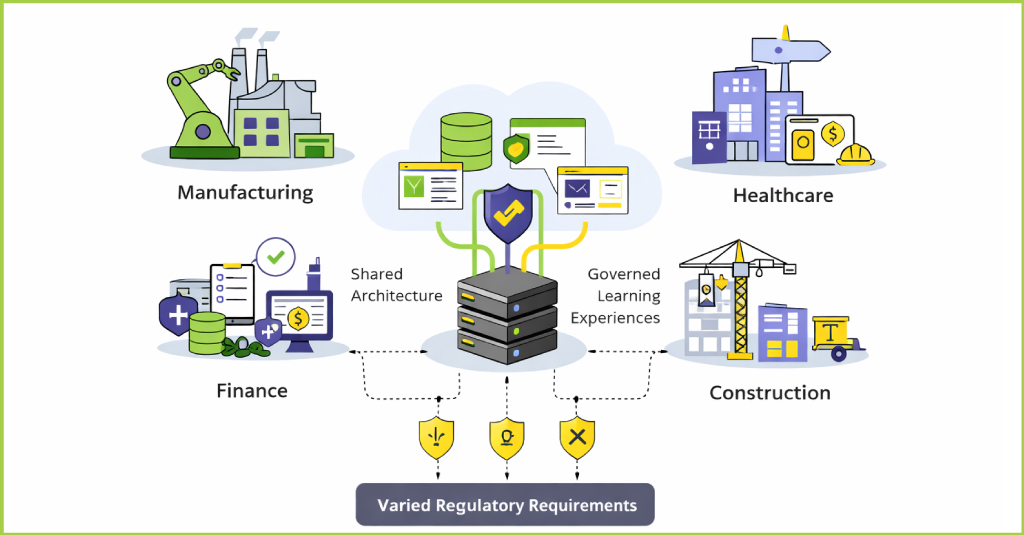

A final source comes from outside the organization. Here, we look at what competitors are doing, or what external sources stipulate as the process. For instance, the International Board for Standards in Training, Performance, & Instruction has developed competencies in several roles such as instructional design and instructor. Other areas have other such stipulations and processes, for better or worse.

A similar approach would be to look at what competitors are doing. This may be challenging for organizations in commerce, but in other fields such as institutions and not-for-profits, such sharing might be viewed as collaborative. Analyses can also be commissioned. These sources, ideally several, need to be collated and consolidated. The resulting list of skills then is a basis for determining how the organization is equipped to execute what’s known to be needed.

Future Needs

The more challenging task is to identify future needs. Some such direction can come from the organization’s intents, as expressed via strategy. Other information comes from analysts and projections. Certainly, too, there are unexpected shifts that require adaptation, whether a pandemic, social/political change, or technological innovation.

For strategic directions, the executive team and associated units may have intents, but they also aren’t necessarily likely to have drilled down to the level of component skills. Thus, this further level of analysis is one area that’s likely to need to be accomplished.

A second source of potential is industry trends, whether specific to the organization’s domain or more broadly. Analysts at both levels regularly provide such analyses, though frequently at a price. Such analyses can provide a good indication of directions that are likely to be seen, particularly if they’re the outcome of a government focus. Not all will be at a useful level and may need deeper definition, but others can include the necessary skills.

Unexpected outcomes are also likely to be analyzed, though there is likely a lag and a lack of accuracy may accompany the initial estimates. These specifications should be looked at with some skepticism, and filtered through the organization’s perspective. As time goes by, the quality of the estimates is likely to improve.

The resulting list of skills, both current and coming, will then need to be internally evaluated to identify needs and prescriptions for either acquisition or development. Having multiple sources, triangulating is a way to build a richer picture than any one approach would provide. There is an inherent amount of speculation in the proposals of future needs, but it’s still better to make an informed assessment than to be completely unprepared.

Organizations should thus be both robust and nimble enough to meet not just the current skill gaps but also in expectation for any future demands. By using skill analysis and triangulation, businesses can create a holistic view of what is needed immediately and what is required in the future to equip them accordingly for the challenges posed ahead. For the sake of understanding in greater depth how skill building fuels organizational performance, you can download our eBook, Skilling for Performance: A Strategic Imperative for Organizations, and learn actionable strategies to build a future-ready workforce.