If our goal is to impact performance, how do we know we’re having an impact? While there are a range of measures, the key is we do need to measure! We need data about what’s happening, to determine whether our efforts have been sufficient or if more iterations of our design are needed. Thus, we need to evaluate what we’re doing.

We also need to be mindful of a couple of things. For one, what type of data do we have access to, and what type of data will answer our questions? Then, we also need to know when we need to evaluate. We need evaluation at several stages of our process.

A critical way to think about it is what answers are needed. Do we need to know whether learners think the experience is good? Or do we need to verify that our interventions have remedied the problem? Matching the data collected to the questions that need to be answered is the best approach. Too often, organizations can collect data that they don’t do anything with! Make sure that you do collect data, but know as priori what questions you’re answering with it, and then do so.

Types

As indicated early on, we need data from our analysis. Specifically, we need to know what our performance should be, and what it currently is. Yet, there are several different types of data we can use. While performance ideally is focused on real organizational impact, at times the needed performance may just be whether it’s good enough so they’ll pay for it, or whether it leads to changes in the workplace, without evaluating the organizational metric. There are constraints within organizations that can preclude getting the desired data. We may have to adjust the data we can collect, though we should be as smart about that as we can.

Will Thalheimer, in his Learning Transfer Evaluation Model (LTEM; available online), expands upon the familiar levels from the Kirkpatrick model. His range goes from whether learners even attend, through asking learners and others what they think, to empirical measures. His eight levels range from several that are insufficient (e.g. learner opinions), through ones that are indicative (such as performance on knowledge tests), to ones that have some organizational validity (so, ascertaining whether they are performing the task). Clearly signaled is that indicators closer to the actual performance in the organization are better for performance.

Further, in his book Performance-Focused Learner Surveys, he elaborates on how, even if you’re just asking for learner’s opinions, there are better and worse ways to do it. In general, in research, there are hierarchies of data: independent objective measures are superior to subjective measures, which are superior to no data at all! Good experimental design about minimizing noise in the data while maximizing the representativeness and quality of the data, hold here.

Just as there are ways to take the same method and be smarter about using it (e.g. asking the right questions), there are also realities about just what we can collect. There are times when just improving learners’ perceptions of a learning experience matters (particularly if you’re charging them for it!). There are other times when you really need to see a change in organizational metrics such as costs or sales. Match your data collection to your situation and need.

Stages

Just as the type of questions you ask can matter when you ask them also matters. As indicated when we talked about analysis, there are evaluation measures you need upfront, to design the solution. Then, there are ones that are used while developing the solution. Finally, there are the data that document the outcome.

At a formative stage, we may be asking detailed questions about the learning process. These questions can range from whether learners can successfully navigate the system (when using new or exotic solutions), whether they’re enjoying the experience, and whether they’re demonstrating a sufficient level of performance in the learning experience.

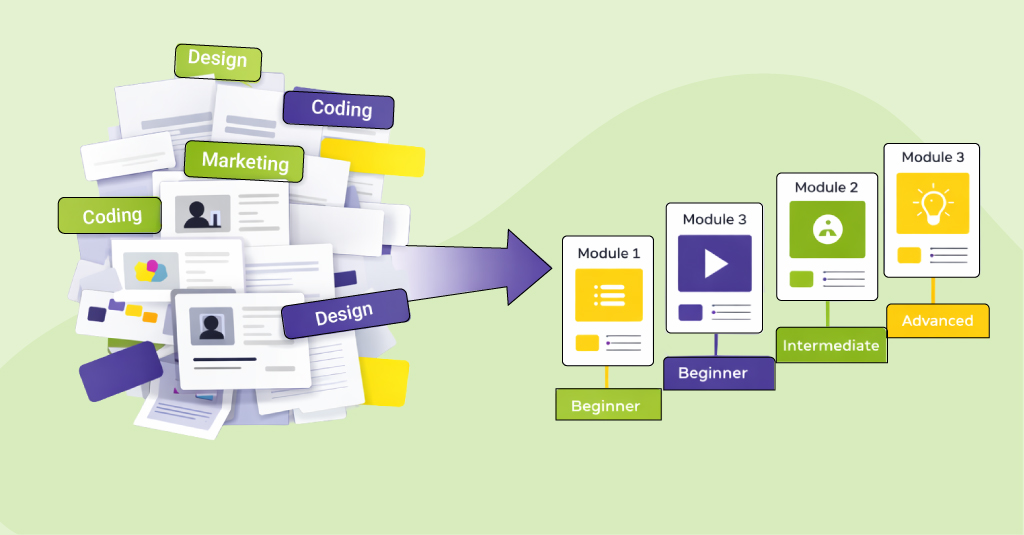

Such data collection is best done iteratively. As mentioned in talking about design, you should expect to test and refine your solution. You should develop your practice first, and evaluate it, before moving on to ‘content’. The data, as suggested, can cover several issues. You may need to adjust engagement, or learning outcome, both, or neither. Expect, however, to need to do some tuning.

You’ll also likely test first the practice, then practice with content, and then the overall experience. Each time, you’ll be testing for greater comprehensiveness of the solution. For performance-focused outcomes, we should be focusing on ensuring that each time we’re making it more likely that the performance outcome we need will emerge.

Then, when our data says that our solution is working, we may (even ‘should’) want to document the outcome. This can be the same as the data saying that you’re done, or you may look for a longer-term view. Overall, from a performance perspective, we should be measuring to see if we’re achieving the outcome we’re striving for.

To effectively enhance performance, it’s crucial to integrate evaluation throughout your learning processes. By thoughtfully collecting and analyzing data, you can ensure that your interventions are not just well-received but truly impactful. Whether you’re assessing learner engagement or organizational metrics, aligning your evaluation efforts with your goals is key to achieving meaningful outcomes. For a deeper understanding of how to shift your focus towards performance, download our eBook, Rethinking Learning: Focus on Performance, and discover strategies that can drive real results in your organization.