When job aids won’t work or have been designed but need training to incorporate them, we need learning design. However, the performance perspective says that we need to emphasize specific elements that might otherwise be missed. Too frequently, our learning perspective has focused on knowledge, not the application. This isn’t acceptable from a focus on organizational success. With the robust result that new information doesn’t reliably lead to a change in behavior, we need to understand what does.

To successfully achieve learning – a persistent change in behavior in the same circumstances – we need to practice that new behavior in those circumstances. Research summarized in books like Ericsson & Pool’s Peak or Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel’s Make It Stick emphasizes the importance of retrieval practice, with specific constraints. Those constraints include spacing out the practice, with increasing challenge, variability in context and task, and more.

From Objectives to Practice

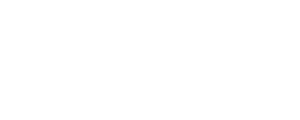

The core focus has to be on the performance as identified in the objectives. The analysis absolutely has to have yielded clear things people need to be able to do, not just know. Then, the immediate next task is to design the final practice. That is, what would indicate a successful acquisition of the necessary learning? This is having them do in practice what they need to do in performance.

From that final practice, what needs to happen is to work backward, identifying necessary precursor practice. For any reasonably complex outcome, it is unlikely that learners will be able to perform successfully on this final task without preparation. If not, why bother with the learning? This preparation includes scaffolded practice; practice simplified in a number of possible ways. That includes parts of the problem being performed, or simpler circumstances such as round numbers or a lack of complications.

The process works back until you get to the stage where learners start. Then you work forward, detailing the required practice. Practical constraints will guide how much practice is required, but the focus should be on achieving a minimal level of competence by the end of the learning intervention. Also consider explicitly how learners will continue to be developed, whether by extending the learning experience via technology, or on-the-job coaching, or both.

The constraints include a number of elements. For one, the level of difficulty should be pitched appropriately. Too simple is boring, and too complex is frustrating. Also, as learners develop, those levels increase. Spacing matters; it takes repeated efforts to improve, with sleep in between; just as you can’t build muscle on one gym visit, you can’t build substantial new skills in one day. Varying the context and task matters. The former supports the ability to transfer the skill, while the latter makes the predictability of the task less, which increases the likelihood of accessing it when needed after learning.

‘Content’

With a suite of practice, the minimal amount of support content matters. Here, there are specific types of content that facilitate performance. This includes models, examples, and the emotional elements of learning.

For one, mental models about how the world works provide the basis for making good decisions in applying the knowledge to execute a task. There are (or should be) reasons why you do things a particular way, and explain why certain decisions are better than others.

The other important elements for learning are the selection, and proper execution, of examples. Examples should show how the mental models are used in different contexts. Research on cognitive load, such as that showcased in Clark, Nguyen, & Sweller’s Efficiency in Learning, shows that examples at the right time for the right learners can improve outcomes over just practice.

In addition to the cognitive elements, we also know that learning works best when learners understand why they should care, and that the experience is a safe place to learn. We need to help learners understand What’s In It For Me (WIIFM). We also want them to feel ok to experience the practice and make mistakes where it doesn’t impact business outcomes.

Iteration & Evaluation

Julie Dirksen, in her most recent book Talk to the Elephant, suggests a myriad of reasons people might not perform even after a course! This suggests that a learning design may or may not succeed. The way to ensure that it does, even following the best prescriptions, is to evaluate and refine.

Research principles provide a good first basis, but aren’t likely to exactly address the particular performance circumstances you need to address. It should be understood by the design team as well as the stakeholders that there should be some testing and tuning as part of the process.

Good practice increasingly suggests that the practice is the first focus of development and testing. Given the key role that critical practice plays in performance-focused learning, this is the most important thing to get right. Then, the associated content can be developed to facilitate success in the practice.

Ultimately, the analysis and design, together, create solutions that should address the performance problems.

In conclusion, shifting our focus from merely imparting knowledge to fostering true behavioral change is crucial for organizational success. Emphasizing performance-focused learning design ensures that new information leads to practical, lasting improvements. By incorporating principles of retrieval practice, scaffolding, and appropriate content support, we can create robust learning experiences that translate into real-world performance. Iteration and evaluation further refine these efforts, guaranteeing that the learning interventions are both effective and efficient. For a deeper dive into creating impactful learning experiences that prioritize performance, download our eBook, Rethinking Learning: Focus on Performance.