To begin a performance perspective, you need a performance-focused analysis. That is, you need to analyze the needs from a goal of achieving necessary performance. Here, we’re drawing from the field of Performance Improvement, and specifically Performance Consulting. Typically, that means you start with a performance gap, an area where you know performance isn’t what it could and should be. Then, you need to understand what barriers are preventing the performance. Once that’s understood, you can move on to identify the necessary interventions. That also includes determining what’s within L&D’s purview, and what instead is someone else’s problem.

For the interventions, you should determine what the resulting change should be, and as a result how your performance metric will change. That implies a necessary first step, identifying what the performance gap is.

Gap Analysis

Gap analysis is the process of targeting a specific performance need. We look at the gaps in performance between what would be desired and what it currently is. It’s also about drilling down from vagaries to specifics. If someone says that they need a sales course, you need to drill down more. Is it the time to close? The success rate? Customer satisfaction. You want to identify any and all gaps.

Gap analysis starts with identifying the core tasks. What are the performers doing, and what should they be doing? It may be that what they’re doing doesn’t match what they should, or they are doing what they’re supposed to be, but that turns out not to be sufficient. Expert performers can be useful here to identify what the performance should look like. Supervisors may be useful here as well to identify what people aren’t doing.

Each gap should be identified with a metric. The question to ask is: how will you know when performance has reached the necessary level? If you haven’t identified an outcome, you really can’t determine that you’ve solved it, and then can’t claim any efficacy about your interventions. While ideally, it’s a core metric such as sales closures or manufacturing errors, it can be subjective such as the customer’s or supervisor’s opinions.

Thus, you should identify the tasks that are to be performed, and to what level. Then you can see to what level they’re being performed now (including zero). This gives you a performance gap. Next, you need a reason for this performance not to be adequate for now.

Root Cause Analysis

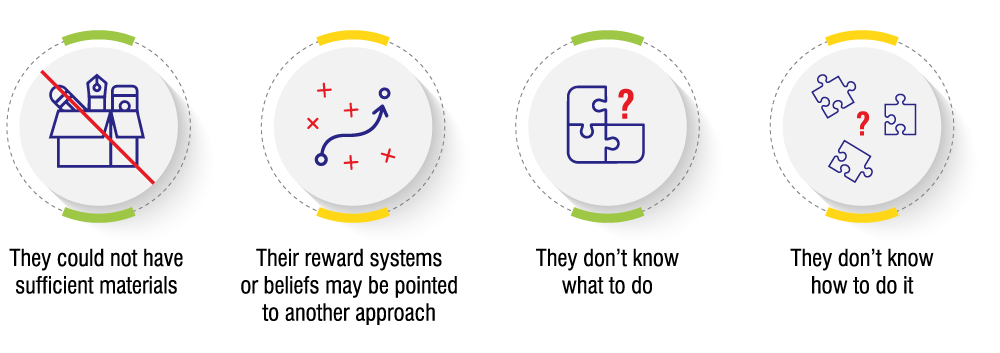

For new skills, the rationale is easy, learners don’t know how to do what they need to do. For other situations, however, there may be more than one reason. If someone, or a team, can’t perform, we can see a variety of potential sources, for instance:

Some of these may have multiple causes as well. If they don’t know how to do it, for instance, it may be that they were taught a different way, or it was so long ago they’ve forgotten, or their boss insists on a different approach. Also, not all of these are amenable to training. Moreover, some may be better served by other approaches, such as performance support.

The important point is to recognize what the barrier is. In Guy Wallace’s The L&D Pivot Point, he cites examples where this analysis indicates the organization needs to do something else first, then come back to the problem. For instance, they may need to rearrange work premises, access more resources, or change incentives. When it is a knowledge or skill task, he then talks about whether to invest in learning or performance support, or both.

There are situations where learning is the right solution, such as when a new skill is needed. Others, however, are where putting information into the world makes more sense, for instance, if something is done so infrequently that learning is likely to be extinguished, but it matters if it’s done right. Another time is when there’s too much information, or it’s changing too fast. Our cognitive architecture, despite its obvious power, has limitations. We’ve developed solutions for them of various sorts, but we need to match the solution to the specific need.

Looking at the actual performance is an important step. For one, you can see how they perform, and ideally, you can also see how exemplary performers work. Another important element is the tools they use. Are they optimized? Another question is whether they are working around a bad process or situation. From interface design, for instance, we learn that post-its on monitors are clues that there’s an inherent problem. They may have solved it (so bake that into your solution), or they’re working around a problem that shouldn’t be there.

Then, there are times when we need both job aids and some formal learning to go along with it. That, in fact, is likely to be the case in more situations than we think; the ideal performance will frequently be how people perform with cognitive tools. Here, you should develop the tool first (if it’s not already part of your work environment), and then the training to incorporate the tool.

Interventions & Targets

Once you know what your intervention is, you need to execute on it. That is, you need to stipulate how the performance outcome is going to be addressed, and what level it needs to be at. You’re not down when you’ve identified the intervention, you also need to ascertain the level of behavior that will be sufficient evidence. Mager defines a performance objective as being comprised of three parts:

- The actual behavior itself, well defined in terms of the necessary performance

- The conditions under which it is appropriate, the context

- The criteria which are used to determine success, or not

One of the best heuristics I’ve heard to define the necessary performance is whether it is observable, that is, that the outcome should be something tangible in action or output. These criteria do not preclude either a job aid or training.

Again, interventions of training or job aids are within the area of responsibility of L&D. Many business units may make their own job aids, but they benefit from a focus on performance. Also, consistency across such instruments is valuable. However, the most important aspect is that such aids are viewed in the context of successfully being used, and that likely includes training. Thus, while other areas can create tools, they should do it in conjunction with, if not actually delegating responsibility to, L&D.

Having identified the core problem and the intervention, then whether it’s learning design or job aid design, it needs to be done right.

In conclusion, understanding and addressing performance gaps requires a systematic approach encompassing performance-focused analysis, gap analysis, root cause analysis, and targeted interventions. By delving into the intricacies of performance improvement and consulting, organizations can optimize their learning and development strategies to drive tangible results. For a deeper understanding of how to effectively enhance performance within your organization, we invite you to download our eBook: Rethinking Learning: Focus on Performance. Let’s embark on a journey towards unlocking the full potential of your workforce together.