ScenariNos

In addition to what we should do to leverage the power of scenario-based learning, there are also steps we should avoid. The ‘nos’ are things that commonly are seen in ineffective scenarios, or that can hinder successful implementation. Ensuring that these mistakes are avoided is one of the success factors to ensure the best outcomes. Some are things that are put in and shouldn’t be, and others are things that people forget to include, but should be.

Errors in Commission

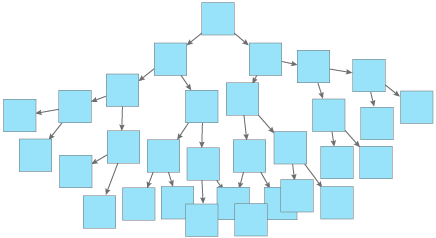

In building scenarios, one of the challenges is keeping track of the branches. There’s a potential for combinatorial growth; with only two options, at 4 levels of depth, you’re already at 15 nodes. One more beyond that and you’re at 31. It keeps doubling, and that’s with only two choices at every stage! The more nodes, the more trouble you have keeping track of them, and ensuring every choice has a plausible outcome.

There are a variety of steps to take to help contain this growth. One is to have terminal nodes, where your choice ends the experience. Another is to have loops, so you can try again. The structure of the situation will dictate the response, to some extent, but if you’re finding your scenario getting long, consider breaking it into multiple scenarios, trimming it. At certain points, it becomes more feasible to build a simulation-driven experience than trying to maintain a voluminous quantity of nodes.

Another mistake is breaking the fourth wall. There’s a strong tendency to want to provide explicit feedback after every choice, or at least the wrong choice. Yet, such a reaction can break the experience.

Consequences should, and characters can provide such feedback, but only if plausible in the story. Allow the experience to conclude, with any and all consequences, then you can provide explicit feedback.

One more thing that can go wrong is developing scenarios as just practice. There are particular skills to employ, including choosing contexts that learners relate to and making believable characters. Similarly, embedding the right decisions in plausible ways and at the right level for the learners are important elements. Displaying the consequences in plausible ways is important as well. Thinking that scenarios are trivial is a big mistake. Treat them as the critical practice that they are.

Errors in Omission

One way to go wrong is to have the choices that learners choose between to be statements, not choices of action. It’s easy to set up a scenario, particularly a mini-scenario with a story, but then ask learners to determine if something’s one of several ‘things’, such as categorizing the situation. It’s a nuance, but the choices should reflect what learners should do, e.g., with such a categorization. Do you then invoke practice X, or do action Y? Make sure you’re having learners make choices that do things, not just think things.

Another problem is not having appropriate feedback. Learner choices should result in a change in the world, and that should be communicated. It’s doubly important that they see the consequences, which reinforces how the world works. That should come before any didactic feedback. Let the good consequences of the right choice, or the bad consequences of the wrong choice, be experienced! On a related note, having didactic feedback (e.g., “action X was wrong”) come before the scenario is finished is wrong. It can be acceptable if it comes from a character in a realistic way, but otherwise, they should just see the consequences of their choices. Even if it would take a while, that can be accommodated in the storyline: such as “Three months later…”.

Not having a plausible situation is also a miss. The situation which the learners are dealing with, even in a fantastic situation (e.g., on a spaceship), should be a recognizable application of the knowledge to a situation they’re likely to face. Learners quickly recognize implausible situations, and their subsequent effort at making appropriate choices diminishes. Keep it real!

The same holds true with dialog. Having folks speak in perfect sentences, with no quirks, is unusual. Informal language is better for learning anyway, but it’s particularly important that dialog sound natural. Different characters are likely to have different personalities and backgrounds, and their language should reflect that.

The nuances matter in making scenarios that will lead to learning. Some of the elements are learning-specific, such as the right situation for the learner to face. Others are engagement, making that situation seem believable. Integrating both is more effort, but the outcomes are worth it when learners are developing the critical skills the organization needs.

In conclusion, effective scenario-based learning is essential for meaningful skill development. Avoid common mistakes in scenario design, and ensure choices are actionable, feedback is relevant, situations are plausible, and dialogues feel natural. For deeper insights, click here to access our eBook: “Scenario-Based: Learning The Ultimate Asset In Your L&D Toolkit” and unlock the key to effective learning through scenarios.