Learning to be a better doctor? Practice some bird watching

As a doctor, you need a set of skills to make a proper diagnosis. Those are the very skills you need for classifying birds.

This is not really about ornithology or medicine. This is about everything where learning is important and concepts like interleaving practice are crucial for learning engagement.

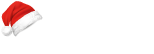

Interleaving helps parse the birds

The Department of Psychology, UC San Diego, explains and recommends interleaving practice, thus: “When you are learning two or more related concepts or skills, instead of focusing exclusively on one concept or skill at a time, it can be helpful to alternate between them.”

Indeed, one of the proven methods to enhance engagement while learning is interleaving practice. It enables more effective fetching of the right piece of memory and its application in a more flexible and productive manner in a new situation.

More specifically, the power of interleaving improves discriminability in those learning bird classification. You need to consider a wide range of traits to identify an avian family. What makes it more complex is that members of the same family need not share the same traits. This is how the book Make It Stick puts it: “Because rules for classification can only rely on these characteristic traits rather than on defining traits (ones that hold for every member), bird classification is a matter of learning concepts and making judgments, not simply memorizing features.”

Making flexible use of knowledge

In his interview to Peter Brown, one of the authors of Make It Stick, Dr Douglas Larsen of Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, explains the connection between classifying birds and making a diagnosis. The variety that helps the ornithologists appreciate the nuances better, helps doctors understand every patient better. “There are many layers of explicit and implicit memory involved in the ability to discriminate between symptoms and their interrelationships.”

As the patient talks, the doctor is sifting through the mental library to see what fits, while also “unconsciously polling” past experiences to help interpret the patient’s description. The diagnosis at the end of it all is a “judgment call”.

Medical education is important—the lectures, the anatomy sessions, and the early rounds in a hospital. Dr Larsen teaches in a school that uses high-tech mannequins and even trained actors to put students through a near-real experience. Everything is assessed—the bedside manner, the quality of interaction and conversation, and the final diagnosis.

More to learning than gathering facts

For those who understand the value of learning engagement, Dr Larsen’s finding will come as no surprise. You end up being more competent at seeing patients in real life if your learning included seeing near-real patients.

Dr Salim Ali, the renowned ornithologist of India had once said: “The man with no imagination has no wings.” Imagination cannot spread its wings if all it has is grains of facts to peck at. It takes engaged learning to be at one’s adaptable best, whether you are getting to know birds or healing a patient.